Tips for assessing last season and planning next season, part two

/In the last article we reviewed suggestions to analyze past workout data. Now for an overview of preseason planning.

Establish training and competition baselines for comparison.

- Maybe very recent or older, like a couple years ago, as long as you have the old data for support.

- Considerations include baseline times for a specific distance, maximum distance, highest average power values, best pacing execution, or just about any factor you would like to see improve.

Find the events you would like to attend.

- Seek out something new. You never know when you might find an event that you like more than your usual races.

Analyze the specific demands of your planned events.

- Course layout

- Distance

- Elevation gradients and totals

- Average temperature and typical weather

Set primary performance goals. Don’t be afraid to set lofty goals as long as they are achievable. These can vary drastically, likely being the most specific for an experienced athlete. For example, it could range from:

- “I would like to finish a marathon.”

- “I would like to finish the San Francisco Rock ‘N Roll Half-Marathon with a time of 1:40:00.”

- “I want to run the Boston Marathon in 3:15:00 with the pace never dropping below 7:30 minute/mile or going faster than 7:00 at any time.”

Set midpoint performance goals to determine if progress is being made. For example:

- Perform a weekly total activity duration of 8 hours and a single longest effort of 2 hours after 8 weeks of training.

- Perform 7:00 minute/mile pace for 8 miles in a threshold/tempo workout.

- Achieve a single day of long distance of 17 miles after 8 weeks of training.

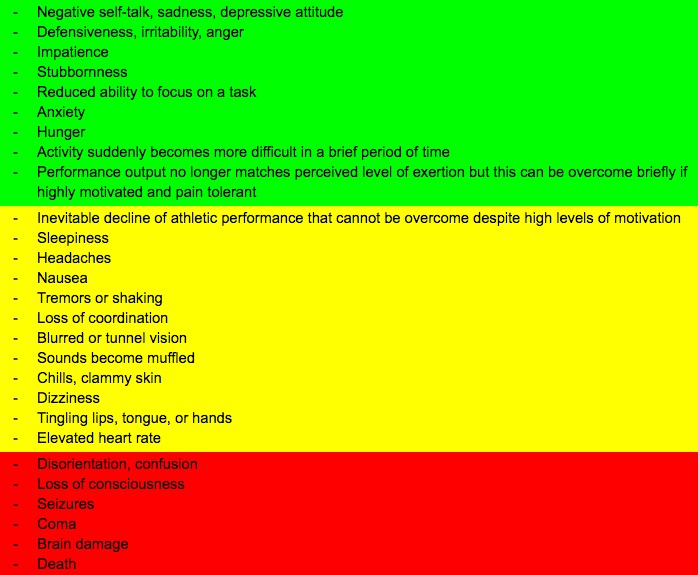

Set the component or technique goals that must be met to achieve the primary and midpoint performance goals. Without executing these component steps, you can’t expect to reach the performance goals. For example (these values are theoretical):

- Consume and tolerate 12 ounces of fluid per hour while at race pace.

- Consume and tolerate 200 calories per hour while at race pace.

- Maintain an average of >170 foot strikes per minute for at least 2 hours.

- Maintain a run power between 200-250 watts for at least 2 hours.

Go slower to get faster.

- I’m a fan of higher volumes of low intensity work with only occasional high intensity work. It’s probably not an accident that professional athletes in any sport lasting for long durations have adopted this strategy. You can’t train hard every day. This is especially the case with older athletes because they just don’t recover as fast as their younger counterparts.

- As you get closer to an “A” event, emphasize increasing the higher intensity work while decreasing overall duration and distance.

If you are planning to do a lot of competing to “race into shape,” you must come to terms with the fact that not every event can be a PR event.

- You will need to give up some hard workouts to do the competitions instead. Define which events are the real priority and just let the others go as hard training days.

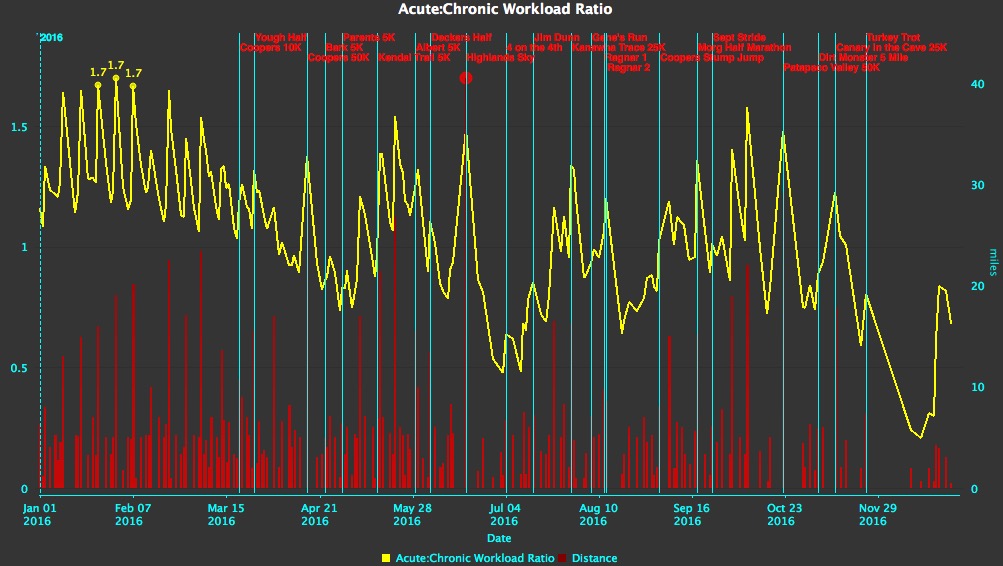

Allowing a longer build period is generally a safer option because it allows for greater physiological and more gradual structural changes.

- Our connective tissues adapt much slower than our fitness. That’s why we often end up with physical injuries instead of metabolic problems.

- Shorter races require less progression time.

- Longer races require greater progression time.

Plan for strength training.

- This overlaps with performing those exercises that the evil PT gave you. I doubt every muscle in your body is at its optimal strength level.

Plan for other cross training.

- Your cardiovascular system doesn’t know what activity you are doing. Your tendons, muscles, and nervous system need to adapt and learn the pattern and load of running to be efficient and prevent injury but performing other types of exercise, like swimming and rowing, will not detract from those abilities.

Involve your friends and family.

- Where would your family like to go for a trip or vacation?

- What events are your friends doing? This might get you a new training partner, which is great if you are occasionally struggling to leave the house in the winter. But it might backfire if you are the one always providing the real motivation.

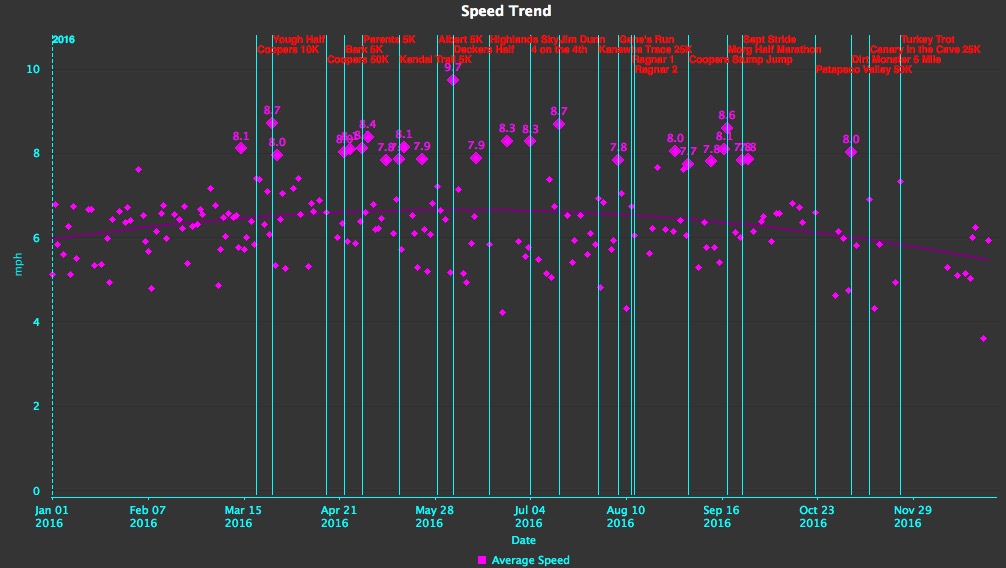

Consider other equipment to more objectively measure performance.

- I get the idea of simplification. Maybe you can and should get by with a basic watch if that has always worked for you. But if you get injured often or can’t seem to break through plateaus, then the extra data from a power meter, GPS watch, or phone app isn’t going to be harmful and may actually help you see where the mistakes are happening. You can always collect the data without looking at it immediately, and analyze it later.

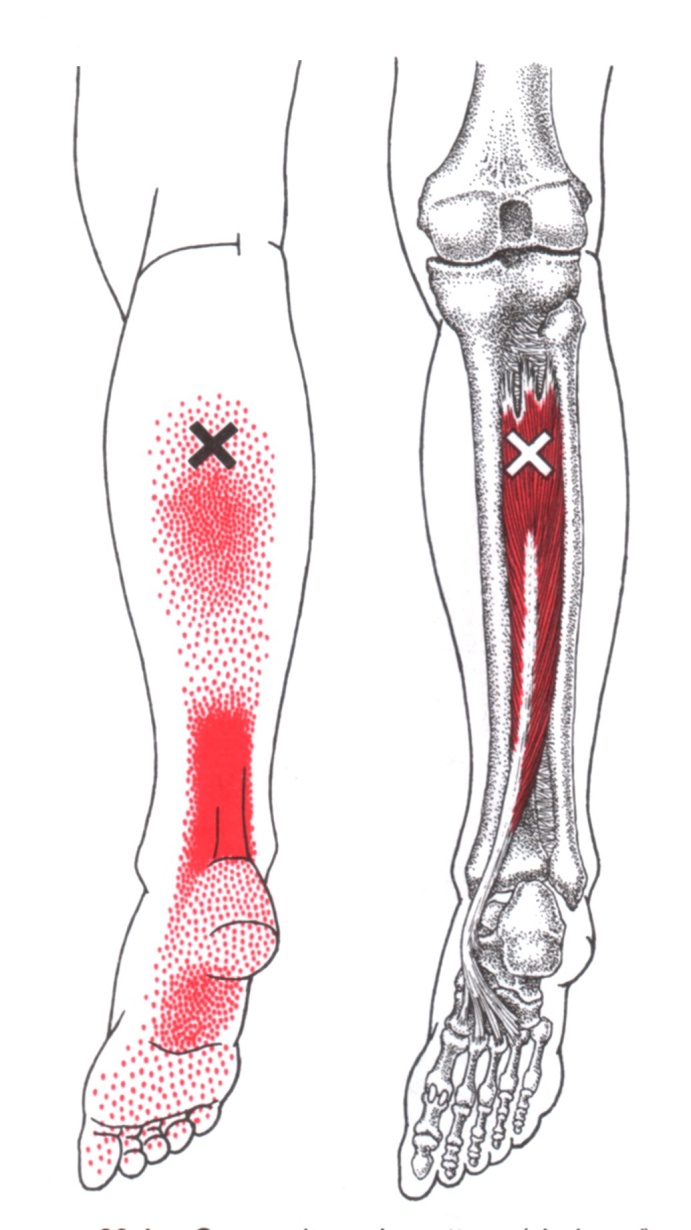

If you have an injury that keeps recurring, get professional assistance to take care of it in the off-season, not a week before your “A” race.

- Most injuries should be objectively improving within a month when properly treated. If they aren’t, there better be a darn good explanation or else I would find another professional to look things over.

- Don’t expect miracles though. Sure, I can often provide somebody help (a.k.a. less pain) in just a couple visits but that doesn’t mean the problem is gone. You have to be reasonable with the rate of improvement and do your homework regularly.

Plan for rest and recovery. If you don’t plan it, you won’t take it.

- Plan for periods of recovery from individual workouts within each week, from blocks of workouts over a series of weeks, and after the entire training cycle that brought you to a big competition.