The art and science of exercising in the summer heat

/Your body is finicky about its temperature, which means it will carry out whatever processes are necessary to stay within the best working range. And that includes slowing you down when you go outside to exercise.

In a hot environment, at rest and with activity, blood is diverted to the skin for cooling purposes via increased sweat production. The sweat on the surface of the skin leads to a loss of heat via convection and evaporation (hooray for science). It’s a pretty awesome and effective system - as long as you aren’t working at really high effort levels or in a really hot and humid environment.

Sustained exercise causes a shift of a portion of our blood volume to the working muscles. And the bigger the muscle used, the bigger the blood supply required to keep it going. Harder efforts will inevitably use more energy at a quicker rate and therefore increase your core temperature to even higher levels than easy efforts. That’s where the sweating mechanism gets a little more inefficient as you are generating more heat than you can get rid of. High humidity also affects the cooling mechanism because the evaporative efficiency of sweating is reduced.

And then we add a third concern: dehydration. Dehydration decreases overall blood volume which magnifies the blood distribution problem further. This means there’s less blood volume for cooling and less blood volume for working muscles. This does not mean you need to go overboard with drinking water, as you could end up in a dangerous state of hyponatremia where you have actually diluted your body’s electrolytes. This ultimately wreaks havoc on your brain function and can lead to death. Some level of dehydration is expected during hard exercise in hot conditions, you just don’t want it to get out of control. Drink to quench your thirst and do not try to drink excess amounts to “stay ahead” of water losses.

Unfortunately, when it’s hot, the body uses more of its stored carbohydrate, glycogen, for energy. This may not be much of a factor for a 30-minute run, but if you intend on racing a marathon you must consider it a factor because you are hoping for your glycogen stores to last as long as possible.

You might think you can compensate for that increased glycogen loss by eating more during longer runs, but there are still a couple problems. One problem is that when the core blood volume is reduced to maintain cooling and supply working muscle, there isn’t much blood left for the internal organs, particularly the intestines and stomach. The other problem is that any carbohydrate you take in while exercising in the heat is used at a slower rate.

With the loss of blood volume to the digestive organs, your stomach might feel like it has a brick in it after deciding (too late) to eat that first gel at mile 10 when you realize you are suddenly feeling woozy. Is it the heat? Are you dehydrated? Was it the pre-race pasta dinner? It’s just poor planning and underestimating Mother Nature.

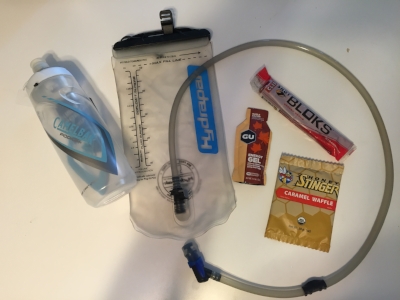

Those gels are meant to be consumed with large amounts of water: 6-10 ounces. Guess how much water is in one of those little aid station Dixie cups? Probably 1-2 ounces. Gels are a very concentrated source of calories, so the proper amount of water needs to be included to dilute them or it will often upset your stomach.

Once the woozy bonking has started, it’s usually too late to get those calories in quickly and maintain your pace, at least for a few minutes. So back off the pace, eat, and then reassess. You can keep the workout from being a complete disaster by making that choice to slow down for a mile and getting in some extra calories and fluids when you first notice a decline in performance and mental state. A slower than expected race finish is better than a DNF, and slowing down on a training day is better than needing your significant other to come pick you up in the car. Nobody needs to see your Road ID bracelet today.

Prevention is the optimal solution for feeling well and having a decent race or training day when the heat is brutal.

Most of us are capable of absorbing around a liter of water per hour but for prevention all you would need to do is drink 16-20 ounces of fluid per hour. I’m saying “fluid” because you may like energy drinks, but realize those don’t always work well in the heat for the same reason the gels can be a problem; too many calories and not enough pure water can slow the rate that fluids are absorbed in an already stressed digestive system.

You should also consume a small amount of calories early and often. Maybe you normally take in 100 calories per hour starting at 45 minutes in a 2- or 3-hour event. Well, you might start at 25-30 minutes instead and try to do it in smaller quantities and at more regular intervals. You might see if you can get in 110-130 calories in an hour instead. And preferably use something you have eaten in hot weather and at a high effort before. There’s nothing worse than experimenting on the day of a competition. Don’t blame me if you haven’t tried these things out before race day.

If you can pull it off, it is wise to use ice and cold water to help regulate your body temperature before and during exercise. During my most recent long run, which lasted 2.5 hours in the middle of a humid 90-degree day, I sat or stood in four creeks for 1-2 minutes each. I’m sure some purist runners would have a problem with mid-run stops, but I consider it a way to ensure success and consistency in pacing for the remainder of the run. You can also chew on ice, use wet sponges or clothing, and place ice within your hat and clothing. If nothing else, the cold is a nice distraction.

Proper pacing or effort dosing is critical in prevention. Expect the worst if you plan to start out at your PR pace on a humid 85-degree day. The calculator at this link can help guide pace adjustments. It’s probably not going to be a PR kind of day but finishing strong would be nice wouldn’t it? It’s also not the kind of day to do speedwork or long, hard pushes in a competition.

A huge part of prevention is regularly having heat exposure during exercise leading up to a particular event. This is the reason why you will experience a disaster day if you always train early in the cool mornings or only exercise indoors at a 65-degree gym. Your body is exceptionally good at adapting to the stressors consistently placed upon it. Try to have the heat exposure for at least two weeks prior to a hot competition or big training day.

Some other thoughts:

- Plan ahead by checking the weather forecast before you head outside.

- Try to exercise in shaded areas to avoid direct sun exposure that will heat you more.

- Figure out ahead of time if you are going to develop blisters from wet socks and shoes by going for multiple brief runs with the shoes and socks wet. Shoes that are well broken-in are less likely to be a problem.

- Wear light-colored clothing.

Clearly, exercising in a hot environment requires your body adjust to not one but many stressors: your working muscles, increased need for temperature regulation, and increased demand on glycogen energy stores. Training or competing in the heat doesn’t have to be dangerous if you are otherwise healthy, well prepared, and plan appropriately.

Seek medical attention if you have any of the signs and symptoms of heat illness:

- Headache

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Pale, ashen, or flushed skin

- Loss of sweating

- Confusion

- Loss of or changes in consciousness

- Excessive fatigue

- Sudden onset of weakness

- Visual disturbances

- Chills

- Severe muscle cramping

- Severe stomach cramping

Stay safe out there. Share this article with all of your exercise buddies. If you have any training questions contact me at derek@mountainridgept.com.