Foot and ankle pain from posterior tibial tendon and muscle injury

/Anatomy:

The posterior tibialis muscle originates on the back of the tibia, turns to tendon, and runs behind the bump at the inner ankle (the medial malleolus), and inserts into several of the bones within the arch and underside of the foot.

image courtesy aafp.org

Function:

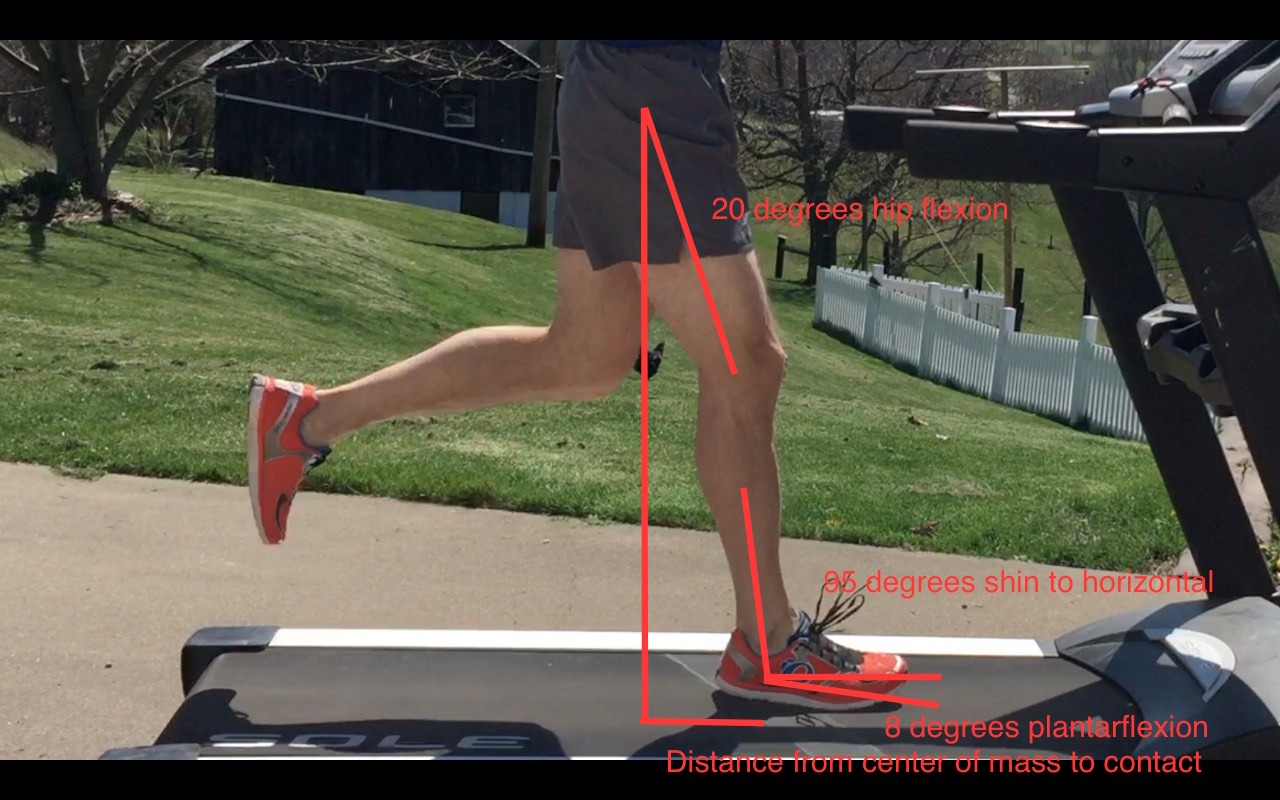

In a standing position, when the posterior tibialis muscle contracts, the inner arch of the foot tends to rise away from the ground. In walking or running the tendon receives its biggest demand when we arrive at midstance and have all of our weight on that single foot. Some pronation during this moment is great for shock absorption but it should meet an end point. That end point is controlled partly by this muscle. This muscle plays a very important role in controlling the amount and rate of pronation occurring at the midfoot.

Causes:

Because the posterior tibial tendon takes a bend around the back of the tibia, the tendon is subjected to tensioning loads as well as compressive loads. To make matters worse, that area of tendon has a poor blood supply.

As usual, progressing intensity or volume of exercise too rapidly is a common finding in people with pain from the muscle or tendon.

There may be weakness of nearby muscles, like the gastrocnemius or soleus, resulting in greater demand on the posterior tibialis muscle.

Some people will aggravate the posterior tibialis tendon indirectly because they lack full ankle dorsiflexion range of motion. By losing motion at this one joint, the adjacent joints can be placed under additional demand. That stress is then controlled for by greater posterior tibialis muscle and tendon activity.

A change in footwear or foot orthotics could be related to onset as the demand on certain tissues could increase.

Poor balance, stability, and positional control of the hip, knee, and ankle may contribute overuse demands to the tissue.

Some people are predisposed to a more flexible and flat foot structure that will, in turn, place greater forces on the posterior tibialis tendon and muscle.

Other rare cases may have a tendon that wants to pop out of the groove that it is resting within, which is associated with a previous traumatic ankle injury.

Signs and Symptoms:

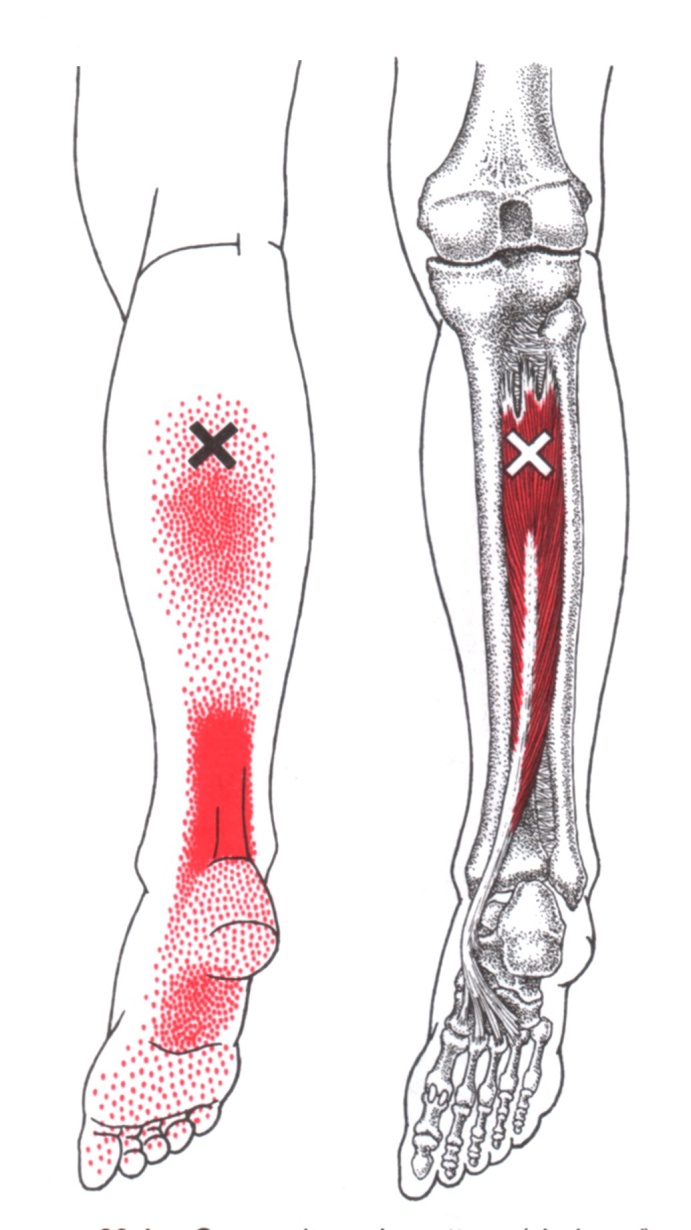

Pain typically comes on without trauma and is usually directly behind the medial malleoli if the tendon is involved but can be at the calf and bottom of the foot if the symptoms are coming more from the muscle. It is interesting to note that an aggravation of the posterior tibialis muscle can mimic an Achilles tendon pain. Take a look at the muscle referral pattern.

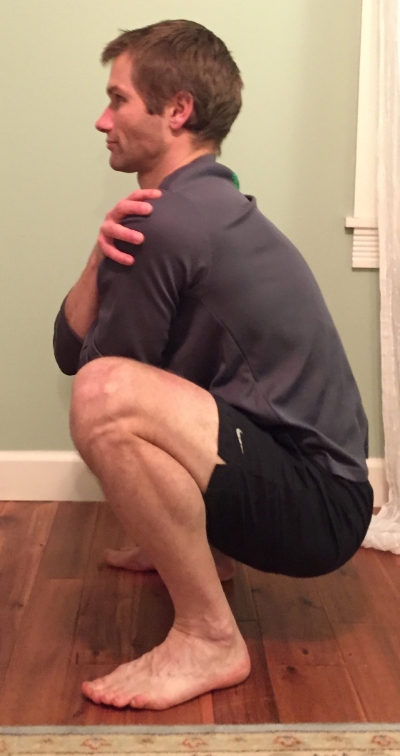

Decreased ankle dorsiflexion motion is common. We would measure the joint angle in the clinic, but consider it a bad sign if you can’t squat fully while keeping your heels on the ground or if you can’t lift your toes and forefoot off the ground a couple inches while keeping the shin perpendicular to the floor. Here I have used a ruler as a reference. The ruler maintains its position while I pull the foot toward my shin. Notice the size of the gap between foot and ruler in the second picture. While decreased motion could be from weakness of the anterior tibialis muscle, shortness of the calf muscles is often a contributing problem.

There may be localized tenderness and swelling just behind the medial malleolus. Especially as the condition progresses, you may notice a clicking sensation at the inner ankle region during ankle movement. This could be particularly bothersome if it is simultaneously painful.

When performing a single leg calf raise there can be pain and weakness, especially at the end point of the motion where the heel should be twisting inward a small amount, as in the picture below. You should be able to perform at least 10 repetitions of a single leg calf raise in a row, one set with the knee straight, one set with the knee bent.

Balance and stability should be sufficient enough to maintain a single leg stance with your eyes closed for 30 seconds.

If the destruction of an early tendon injury worsens, the inner arch will flatten as the tendon lengthens abnormally, causing a “flat foot deformity.” This is the reason you really want to catch an injury to the tendon early, before any long-term structural changes have occurred. If the normal structure has been modified then you will have a much longer road to recovery.

Other possible or related problems:

Pain at the inner ankle and lower leg can also be caused by a few other issues. This is where seeing a trained professional helps to rule out these other problems. If you are experiencing severe pain, numbness, tingling, pins and needles, general calf swelling and tightness then definitely don’t try to self-treat.

Ankle sprain

Blood clots in the lower leg

Sciatic nerve compression and irritation

Lumbar nerve compression and irritation

Tibial nerve compression and irritation

Sacroiliac joint alignment/stability problems

Hip region muscle trigger points/muscle tissue dysfunction

Flexor digitorum longus tendinopathy/trigger points/muscle tissue dysfunction

Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy/trigger points/muscle tissue dysfunction

Abductor hallucis trigger points/muscle tissue dysfunction

Loss of hip mobility from decreased muscle flexibility or hip joint problems

Fracture or stress fracture

Tarsal tunnel syndrome

Treatment:

General treatment goals are going to consist of some combination of the following:

Decreasing pain

Increasing lost motion

Increasing stability and balance

Increasing muscle and tendon endurance

Increasing muscle and tendon strength

Resolving any abnormal movement patterns

Preventing recurrence

Short-term rest, ice, and NSAIDs are generally appropriate in healthy people for immediate care of a new injury to decrease pain. I am always going to emphasize that it is important to determine why the injury occurred in the first place as these methods do nothing to address the real causative factors.

Supporting the arch of the foot during the stance phase of foot strike can be helpful in decreasing load on the posterior tibialis temporarily. This can be achieved with taping, temporary or permanent foot orthotics, and footwear modifications. You should not become reliant upon these devices to keep your deficits at bay forever, though.

Strengthening the posterior tibialis muscle and tendon can be a beneficial method to increase tissue integrity. The most common strengthening method for a moderately calm tendon is a single leg calf raise performed with the knee straight and the knee bent. If that is too painful, the individual can perform these with double leg support or perform ankle inversion with a cuff weight or band until the calf raise can be performed with moderate or no pain. When strengthening tendon, the current research indicates that it is acceptable to cause mild discomfort in the area of tendon injury but you would not want to push the tendon so far that it remains painful for hours or worsens the following day. In many people holding the topmost portion of the calf raise for 15-30 seconds, known as an isometric, can help decrease pain.

There is no substitute for having full ankle range of motion. If ankle motion is lost, you may need to work on a combination of stretching, joint mobilization, and other soft tissue work to regain mobility. Soft tissue techniques are of benefit to improve any excess muscle tissue tone and gain length. This includes foam rolling, massage stick rolling, massage, myofascial release, and dry needling.

More aggressive treatment can include the use of a walking boot for immobilization and corticosteroid injections. These injections will coincide with a risk of tendon rupture, however, and should be avoided if possible. Another type of injection is PRP (platelet rich plasma). Some physicians will provide patients with nitroglycerin patches to improve local blood supply to the tendon. Surgical intervention is the last thing you want but may be particularly necessary if the tendon has remained inflamed for such a long period that it cannot glide smoothly in its sheath or has split longitudinally. A newer minimally invasive procedure to help chronic tendon injuries is called Tenex.

Please share this article with your running friends! To receive updates as each blog comes out, complete the form below. And if you have any questions, please email me at derek@mountainridgept.com.