Knee pain at the iliotibial band: What can you do about it?

/Description: Iliotibial band syndrome, or ITBS, is one of the more common injuries affecting runners. And why is that? Probably because the same faulty motor patterns and muscle weaknesses tend to run rampant amongst many runners. ITBS tends to come on gradually, causing a lateral knee pain, though some runners are able to bring on the pain in a single run of greater distance or intensity than their typical. It is often another story of too much, too fast.

Anatomy: The muscles that attach to the ITB are from the hip and thigh region: gluteus maximus, vastus lateralis and tensor fascia latae. The far end of the ITB splits into several sections, which indicates it has a role in the function of many areas. Most commonly athletes will complain of pain where the ITB interacts closely with the lateral femoral condyle.

Cause: The primary function of the ITB is to stabilize the knee during walking and running gait. When some of the hip muscles are weak, the ITB can be relied upon too heavily for knee stability, thus stressing its lower attachment excessively.

Signs and symptoms: The far end of the ITB can flare up like a tendonitis does when initially becoming inflamed. There can be inflammation at the bursa that sits beneath the ITB as well. As a result, you might notice swelling and tenderness to touch at the outer knee where the ITB crosses. There can be a snapping or popping sensation at the lateral knee. The pain tends to take on a sharp and stabbing quality when there is demand placed on the leg but the general area may be achy after use.

A common finding in many instances of ITB syndrome is hip muscle weakness, particularly of the gluteus medius and gluteus maximus muscles. There may be a decreased ability of the nervous system to activate and control those hip muscles while running, even if they are strong in testing.

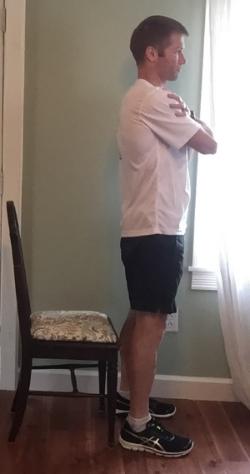

An indicator of poor gluteus medius activation is an excessive dropping of the opposite side of the pelvis when the affected leg is in stance. One way you can check this is to stand in front of a mirror, hands on your hips, and then shifting yourself onto one leg. For instance, if you move onto the left leg and the right side of the pelvis clearly drops then you have a positive Trendelenburg's sign. Check both sides as it is common to have an asymmetry. In the video below I demonstrate both the active position and inactive position. The same excess of pelvic motion can occur in walking and running.

Solutions: As with many of these injuries, there is no magic pill and no quick fix. Consistent but brief supplemental work is the reliable solution.

1. Some physicians may promote injecting the bursa region that lies between the femur and the end of the ITB. Corticosteroid injection should be a last resort as recurrence is very likely if the mechanical control of the hip and knee are not addressed. I have had patients where injection was used as a first line treatment. Guess what? The pain came back. At least this is a lower risk area to inject with corticosteroid as the risk of ITB rupture is minimal compared to an area like the Achilles tendon or posterior tibialis tendon. The side of the quadriceps is probably more likely to rupture. Remember, injections do not address the mechanical reasons the injury occurred in the first place.

2. The very first and simplest issue to address is the presence of any weak muscles at the lateral side and back of the hip. These muscles need to be activated easily and consistently by the nervous system. So many people have weak muscles around their hips, trunk, and pelvis so don't assume you are an exception. It is a daily occurrence for me to see these issues in the clinic.

Athletes need a baseline level of strength and the ability to effectively recruit these muscles while running to prevent the pelvis and hips from destabilizing. Poor strength or activation may allow the thigh to collapse inward or rotate inward along with an unleveling of the pelvis. It’s also important to consider the endurance of these muscles because the strength will undoubtedly be decreased a few miles into a run or fatiguing workout.

As a side note, I have seen so many patients that were correctly told to perform exercises like a side lying straight leg raise only to discover they are doing it in a manner that works the wrong muscles because no one checked their technique. Their form was incorrect and doing these exercises incorrectly can actually contribute to the problem. Not only are the wrong muscles used (eg. tensor fascia latae), they are creating a dominance in areas that further inhibit the function of the correct muscles (eg. gluteus maximus).

Here's the routine that I do on a weekly basis.

3. As the awareness, endurance, and strength are all starting to increase, it is necessary to challenge the nervous system’s ability to stabilize the hips and pelvis. Single leg balancing activities are a great program component to do this. The individual must recognize where the pelvis achieves a stable position in order for this to be effective. This can progress to single leg hopping and jumping activities while keeping the pelvis stable.

4. There has been some controversy over whether athletes should foam roll their ITB, which I discussed previously here. Don’t bother trying to stretch your ITB unless you like to waste time and potentially worsen the problem. Most ITB stretches simply stretch the hip muscles that are already weak, which is absolutely counterproductive. And the ITB’s connective tissue is extraordinarily strong so you aren’t going to stretch it.

image courtesy 220triathlon.com

5. Running technique changes can be effective to normalize demands on the hip muscles and move in a less painful range of motion. The knee needs to maintain a high level of bend during swing. If you have a tendency to overstride far forward of the body’s center of mass then you will place greater demand on the gluteus medius muscle as soon as the foot makes contact, setting yourself up for failure. You may only need to increase your cadence 4-6 steps per minute and think of nothing else. There’s more information on cadence changes in my shin splint article here. The relationship of the ITB to the femur bone beneath it also changes as the knee is bent and straightened so changing the technique can change that relationship. In some runners there can be a benefit to running quickly for 20-30 seconds and then walking to vary the mechanical position of the ITB to the femur.

Poor right hip abductor engagement

6. If you have been unable to exercise secondary to ITB pain, make sure you take full recovery days between the days that you do start to exercise. These off days are great to emphasize the strengthening, balance, maintenance, and so on. For running that first time back, short and consistent is the name of the game. Better to run one mile each on three or four days than three to four miles at once. Depending on the number of days you have taken off, a mile isn’t an unreasonable distance to start at and that may also require a walk/run program.

Please let me know if you have any questions at derek@mountainridgept.com.