Strength Training for Runners, Part 3: How?

/So hopefully I’m persuading a few runners to try adding strength training to their regimen. Let’s go over some general strength training tips and the primary objectives to consider for the various muscle groups.

Strength training tips and objectives

1. Your primary goal is to place a stress on the body that it isn’t accustomed to and that, in some ways, exceeds the stress that running places on the body. This demand is what leads to positive adaptations.

Efficient running is stressful for the muscles, tendons, bones, joints, and other tissues in the body.

Inefficient running is even more stressful on many of these structures, which means you want to either get rid of the inefficiency (ideal) or make your body more tolerant of it (not ideal).

2. The progression should go as follows: mobility → skill → stability → endurance → strength → power

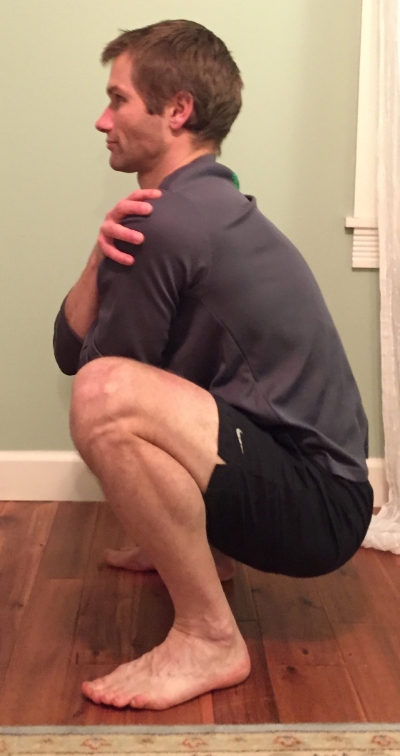

This means you need to master the basic movement pattern with a full range of motion far before you attempt to move heavy amounts of weight or move explosively.

Running requires tons of repetitions of a powerful movement yet many people don’t have the basic mobility and strength down to safely use that power.

3. Circuit train, especially if you aren’t accustomed to strength training yet.

Runners love to stay moving, so your earliest forays into strengthening can emphasize circuit training of the entire body. Circuit training allows you to move right from one exercise into another, bringing the heart rate up and providing a similar feel to the constant work of running that we crave.

Circuit training is more reasonable from a time-management perspective.

If you are new to strength work, alternate upper body, lower body, and core exercises to let each muscle region recover effectively in between exercises.

More experienced athletes can stack a single set of two or three similar exercises together to increase the muscle demand. For example, lunges followed by single leg squats and then on to step-ups.

You can add plyometric and agility drills throughout the strength session to keep the heart rate up and integrate running with speed, which is discussed next.

4. Integrate strengthening into your run workouts to improve your awareness of how to use those muscles while running.

Going back to circuit training, here’s one of my favorite winter activities when the weather is horrible and I must run inside:

Treadmill run 5 minutes

Hip strengthening and stability 1-2 minutes

Core strengthening and stability 1-2 minutes

Leg strengthening 1-2 minutes

Wash, rinse, and repeat for 45 to 90 minutes total

Perform a couple of bodyweight resisted exercises like leg raises or planks during your warm up to emphasize core and hip stability, strengthening, posture correction, and muscle awareness.

5. The abdominals (and actually some hip muscles) are primarily stabilizers when you run so learn to use them in that way.

Instead of crunches or sit-ups, use variations of planks and bridges.

Emphasize single leg activities with the pelvis held in a level position. I reviewed the pelvic position last week with the Trendelenburg's sign.

6. Work one side of the body at a time.

Symmetry in muscle strength is a key point. Working both sides of the body at the same time is less challenging and less productive because you will inevitably use a more dominant side without even realizing it.

7. Work multiple muscle groups simultaneously by emphasizing “closed chain” movements.

Closed chain implies the end of the leg or arm will be in contact with the ground or fixed object. Examples include squats, lunges, push-ups, step-ups, power cleans, planks, pull-ups, and most plyometrics like jumping and hopping.

Closed chain movements mimic running and normal daily activity. Open chain exercises, like leg extensions, do not often duplicate our day-to-day movement.

8. Think about performing exercises by the plane of movement that you move each joint through and then do a little work for each plane.

Squats and lunges emphasize a forward/backward plane at the knees and hips.

Single leg hip rotations emphasize a horizontal plane at the hips.

Pelvic drops emphasize a side-to-side plane at the hips and trunk.

9. When an exercise has become too easy, add an element to decrease stability and see if that doesn’t increase the difficulty.

For example, a standard front plank is easily advanced by lifting one leg, one arm, or both at the same time. The idea is to increase the wobble factor.

Some equipment options to increase instability include swiss balls, BOSU balls, and wobble boards.

Many standing exercises can be performed on a single leg to challenge the stability but you need to be proficient with their double-legged versions first.

10. Avoid using machines, emphasize free weights.

The limited range of motion keeps you from working in the positions that you actually need to gain usable strength.

Machines do not challenge the stabilizing muscles and nervous system components that can be beneficial for injury prevention and optimal performance.

Free weights are more likely to mimic the tasks that we perform in daily life because we commonly lift and move heavy objects.

11. Reduce strength training loads primarily in the week before your “A” races but not before “B” or “C” races.

Strengthening is part of the constant stimulus that you are trying to adapt to, so you don’t want to recover excessively before your low priority events. Train on through.

While training just before a low priority event you can decrease the number of repetitions in a set by 3-5 but keep the weight the same.

Before an “A” race, decrease both the sets, resistance, and repetitions if you have been working with resistances that cause failure at higher repetitions (i.e., do only 1-2 sets of 15-30 repetitions instead of 2-3 sets of 15-40 repetitions). If you have been gearing up with really high loads and performing more powerful, explosive moves, then back the sets down and the resistance only slightly (ie. do 2-5 sets of 3-8 repetitions instead of 5-6 sets of 3-8 repetitions).

12. Once your priority event has passed, back off of the rapid power and agility movements and encourage basic strength and strength endurance again for 2-4 weeks.

13. Perform strength training on shorter or less intense running days, especially if you have never strength trained before.

We don’t need too much of a good thing. Too much exercise stimuli in a day or series of days is a recipe for injury.

I often still use running as a brief warm-up before strengthening and, as mentioned, incorporate running drills throughout the strength workout.

Strength days are a great time to do other cross training on a bike, elliptical, rower, rock wall, or anything that allows you to experiment and break up the monotony of running.

14. A general initial strengthening structure could consider spending:

50% of the time on the large primary movement muscle groups that undergo heavy use in running to improve overall movement strength and strength endurance.

These muscles, like the quadriceps, gluteus maximus, and hamstrings, can be pushed harder with higher resistances.

25% of your time focusing on the muscle groups that are not dominant and become neglected in the running motion to prevent injury.

These muscles, like the deep gluteals, usually require very little resistance because they are not large or power producing.

25% of the time integrating plyometric drills to increase power output, speed, and agility.

15. Allow at least 6-8 weeks of working at least 1x/week for noticeable performance changes.

In next week's blog I'll go over more application specifics and exercises.

Please let me know if you have any questions at derek@mountainridgept.com. If you enjoy reading these articles and applying them to your training, please “like” the Mountain Ridge Physical Therapy Facebook page.