Calf pain in runners: 9 causes and considerations From footwear to form

/One of the most common complaints runners have is calf pain, particularly while running. It might initially come in bouts during just a couple runs, but sometimes it will stick around for weeks and months if left unaddressed. Rest usually improves this discomfort at first, but isn’t typically sufficient for long-term, consistent relief if the person continues to run and doesn’t make any other changes. They’ll complain that their calf muscles feel “tight.” And it’s common for both calf muscle groups to start to feel this way around the same time.

Some runners take the “I give up” approach and assume it’s a necessary part of getting older or running too many miles, so they begin to modify their training around it by planning an additional rest day or cross training instead. They take the “a little running is better than no running” approach, which I think is very reasonable for a true injury, but when something can be improved, why not address it the right way?

For the sake of this article let’s assume we are covering muscle-specific pain in the calf that isn’t too bothersome much outside of running. These are more likely to be muscle overuse syndromes or biomechanical overload syndromes. This cause of pain can be treated while you continue to run, if done correctly.

But there are plenty of other things that can cause calf pain and you will need a medical professional, not an internet article, to rule those out.

Possible (and Potentially Serious) Medical Issues to Rule Out

Blood clots/deep vein thrombosis

Nerve mobility deficits or irritability of the lumbar, sciatic, and tibial nerves

Calf muscle tear/rupture

Popliteal artery entrapment

What can you do?

Seek professional medical guidance if you have had a traumatic injury (often accompanied by a sudden “pop” or a feeling of being kicked in the calf). We are also very concerned if there is a more persistent or severe onset of pain, or additional symptoms like sensation changes (pins, needles, tingling, burning), fever, swelling, and redness of the calf. It’s important to consider your overall history because factors such as being older, having a history of a particular problem, recent immobilization, comorbidities, and certain medications can all have a role. These issues are very different than a mild discomfort, tightness, or fatigue that occurs only while running. It isn’t to say that some of these problems can’t be treated conservatively but you will have the best chance at success with proper diagnosis. We need to keep in mind too, if you have attempted treatment that doesn’t seem to be helping.

Other considerations:

Calf Strength and Endurance Deficits

Logic would tell you that running demands a ton of work from the leg muscles. At some routine level of activity, the muscles adapt to that work and you keep on going from week to week without issues, just as happily as ever. Now what happens if you chronically demand so much from those muscles that they can’t adapt to what you are trying to have them do? They slowly start to...change…like your best friend from junior high school. At first it was cute but two months later you were just annoyed. The muscles don’t have to be painful, at first. Maybe they just feel more tired and tight. But when you keep running on them and don’t make any other changes they become more consistently problematic.

The muscle and fascial connective tissue isn’t able to adapt to your demands in a positive manner when demand outpaces normal repair over a long period of time. Why couldn’t the muscles withstand the demand? Most likely there wasn’t enough strength or endurance (or both) in the muscle group. Given enough time of chronic repetitive stress on under-prepared tissue, the quality of the soft tissue changes.

Running really requires something called “strength endurance” from muscles like the calf. You might even better call it “strength and power endurance,” but I don’t want the top of your head to blow off right now so forget I said that. The point is that the muscles of the calf have to withstand high forces (strength), very rapidly (power), and with high frequency (endurance).

The calf-strength variations that will show up when tested during a single leg calf/heel raise are often interesting. A runner might have tons of gastrocnemius strength during a straight-knee calf raise, but when the calf raise is re-tested while the knee is flexed, they can’t reach the top end of the calf raise anymore. Often this means they have decreased soleus strength, which is a real problem since, while running, we spend a large portion of the running stride with the knee slightly bent. Or maybe they can’t perform the same amount of reps on one side when compared to the other in either position.

Even worse is when the person can’t perform any type of single leg calf raises without relying on their long toe flexing muscles that come from deep in the calf region. My heart hurts when I see this. These people tend to grip with their toes during calf raises and just can’t get their brain to shut those muscles off while completing the raise because the bigger, outer calf muscles are just that weak. It’s not a surprise that people will run with those toe muscles engaged heavily too.

What can you do?

Build the strength of the calf muscles using calf raises, with the knee slightly bent and straight, without gripping with the toes, and with just a single leg at a time. Full ankle range of motion is key. Causing calf muscle fatigue is the goal. That might take five reps or 20. Don’t hammer it to death because you’ll probably become sore for two days. Early strengthening with bodyweight is good but after 2-3 weeks of 3-4x/week, runners should be able to add extra resistance, even beginning with something like 10 pounds. The calf needs to be strong, but...

Other Strength Deficits

I am stating the obvious here, but it takes more than the calf muscles to propel a runner. Lacking hip or thigh strength could lead to a trickle-down of abnormal demand into the calf muscles. The calf could actually be super strong but just have to endure too much stress every time you go running because something else stinks at its job. End result: too much work being done by the calf muscles that leads to stress-induced discomfort.

What can you do?

Ensure you have full strength of the hip and thigh muscles (eg. gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, hamstrings, quadriceps). Strengthening exercises for these areas is beyond the scope of this article, but the point is you need to look outside the area of symptoms if you want to actually fix the problem. Remember to emphasize single-leg strengthening to ensure symmetry. If you can only do eight single leg bridges on one side and 20 on the other then you’ve got some extra work to do on the weaker side.

Neuromuscular control

Your awareness of and ability to modify the way your body moves at any given instant is a good indicator of overall athleticism. Remember, our muscles only know how to function based on what they are told by the nervous system, particularly the spinal cord. If your nervous system can’t figure out how much force to generate from the various muscles at any one moment then your movement isn’t refined. Picture a gymnast on a balance beam. It doesn’t take much error to result in falling off the beam. They really have to own their movements with precision and certainty. Kinda, sorta knowing where their feet are isn’t going to cut it. Or imagine an infant learning to crawl. They are constantly on the edge of failure until their nervous system figures out the best way to coordinate muscle contractions to keep their body stable. Your calf muscles must contract with correct amounts of other muscle contractions in that leg with every footstrike.

What can you do?

Working on drills to improve your balance and proprioception is key. As previously mentioned, single-leg work is a necessity. And I don’t mean sit on a machine to do knee extensions, calf raises or leg presses one leg at a time. When you use machines, there’s no real demand that requires the nervous system to learn how to stabilize your body. Single leg balance that progresses into single leg deadlifts, single leg squats, single leg hops, single leg box jumps, single leg calf raises, the options are many. The point is to emphasize standing on one leg while you move the rest of your body.

Foot, Ankle Structure

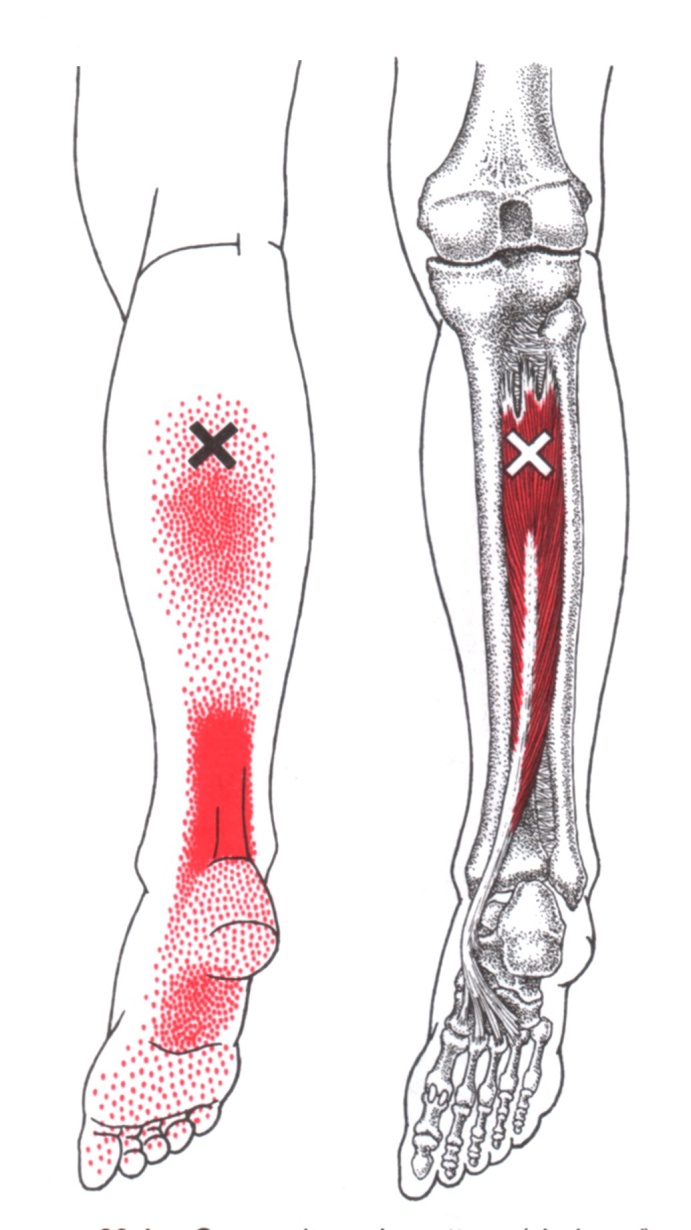

An individual with a more flexible foot or ankle type that allows an inward collapse of the heel bone or inner foot arch could be placing more demand on their calf. These people are generically labeled as “flat-footed.” Though the more superficial calf muscles are mainly producing force for the forward/backward sagittal plane, there are additional forces that this outer calf and much deeper calf must withstand in the side-to-side or frontal plane. And then we must consider that the deeper calf muscles, like the posterior tibialis, that help to control the side-to-side ankle and foot motion, are also notorious for being part of the cause of pain.

What can you do?

Build the strength of the muscles that assist in stabilizing the ankle and foot that also come from the lower leg, like the peroneus longus, peroneus brevis, anterior tibialis, and posterior tibialis. One way of doing this is with resistance bands. This is also why I love single leg strengthening exercises like single leg Russian deadlifts that also require a person to balance and stabilize like a circus elephant on top a ball. As discussed below, you should perform routine soft-tissue maintenance on all of the calf muscles, superficial and deep.

Maintenance Habits

Here’s a big one. So you run for hours at a time or try to run really fast, essentially beating down the calf muscle fibers and their surrounding fascia and tendons, but then you don’t do anything good for those tissues? Resting is supposed to fix it all? It probably would if you weren’t trying to run most days of the week.

What can you do?

Buy and use a massage stick, foam roller, or lacrosse ball to routinely massage the muscles of the legs. Be sure to emphasize routine soft tissue maintenance for every major muscle group. The technique doesn’t matter as much as just doing something positive regularly for the muscles to keep them more supple and loose. Before the pain rules your life. Once the pain is consistently present, I can use techniques to get it to go away quickly and then you need to take over with a maintenance program.

Calf Muscle Length

In many instances, you can think of calf muscle length as an indicator of something besides true structural muscle fiber, fascia, or tendon length. The chronic abuse of running very often leads your nervous system into thinking a higher level of nerve-dependent activity is needed in the calf when it really isn’t. That keeps the fibers holding a greater tension at all times, which makes the calf muscle appear shorter than it really is structurally. So there’s a big difference between your nervous system telling a muscle to behave as if it is tight and a muscle that truly, structurally is short and tight. Weird, I know.

What can you do?

Calf stretching with the runner’s stretch or dropping your heel off a step is typically what runners choose to do if their calves feel tight. But if you want a change in actual muscle structure and length, be prepared for it to take multiple weeks of frequent and prolonged stretching. Like three 60-second stretches at least three days per week. A deep full squat will more likely max out the ankle joint motion and soleus muscle length while a straight leg heel drop on a step is meant to be a gastrocnemius stretch. But I would rather rely on the other soft tissue techniques mentioned above as maintenance, like self-massage, myofascial release, or dry needling to make the muscles relax, which automatically improves their length in many people. Remember, the goal probably doesn’t need to be improving the muscle fiber lengths, it’s convincing your nervous system to let the darn muscle relax.

Running Technique

Certain techniques tend to stress certain tissues more over time - that is neither bad nor good. If there were ever a predictable running method to stress the calf muscles, it would be a forefoot initial contact style, particularly if the runner doesn’t allow the heel to reach the ground after making contact. With about 2.5x to 3x your bodyweight coming through the limb while running, there are huge lengthening or eccentric forces coming through the calf tissue when the forefoot touches the ground before any other part of the foot. This could be the case with midfoot striking too. Depending on the runner’s individual style though, midfoot contact can decrease calf stress. Heel striking itself doesn’t necessarily tend to load the calf the same way a forefoot contact might, but rest assured those people have their own set of problems at the knees, thighs, and hips. Overstriding, which commonly accompanies heel striking, can be more stressful though.

What can you do?

By choosing to use a forefoot contact you should know the calf area is at risk for injury and perform your due diligence with the maintenance just mentioned to keep the calf muscles loose, relaxed, and happy! You may not immediately need to modify your technique to a heel or midfoot strike but could do so temporarily to maintain running fitness until the calf muscle status has been improved. Overstriding needs addressed in any instance. This is where we often need to address hip strength and control, hip flexor length, and other possible issues throughout the entire leg.

Paces, Distances, Training Program Design

What type of running have you been doing lately? Fast, slow, mixed speed, uphill, downhill, shorter distance, longer distance? Are these methods what you have always done or has your training changed recently to incorporate more speedwork, racing, or hills?

What can you do?

If you changed your distance, terrain, or speeds, and the changes contributed to the symptoms, temporarily remove or decrease those stressors for a week or two. Uphills and running faster are the most potent instigators of calf pain. Know the threshold of when the pain would begin while running and then try to stay just beneath that point for a couple weeks while the strengthening and other soft tissue treatment take hold. Be sure to have a full recovery day without sports or running that doesn’t stress the calf muscles.

Footwear

So you thought the zero drop or minimal shoes were great choice? Well, they are, but not if all this other stuff is off and you suddenly change the shoes too. They cause at least a 10% increase in calf load compared to a traditional shoe. Add that onto your already lackluster muscle tissue quality and we have a recipe for trouble. This is also an issue for runners when they switch suddenly from their base training shoes into their racing flats or spikes for competition.

What can you do?

Work your way into minimal or zero drop shoes gradually if you haven’t used them before. Two or three runs per week of 5-10 minutes is plenty in the first month. Run your warm up with them and then switch into your old training shoes. Gradually add faster workouts with spikes and flats into your training instead of just competing in those shoes. Spend more time barefoot at home and be sure to do the maintenance piece mentioned above to get the muscle tone to decrease. Here’s a nice article on transitioning to minimal footwear.

If you enjoyed this article, please take a moment to like us on Facebook and please share it with your running friends!