17 tips for your COVID-19 quarantine from a sports medicine professional

/One of my duties as a healthcare professional is to help keep people healthy, but that’s especially important as we enter a period of massive uncertainty. While I might not be able to follow you around and provide hand washing reminders, I can give you some helpful health recommendations. So what are you to do during your COVID-19 lockdown?

Wash your hands. Don’t touch your face. Don’t pick your nose. Don’t put your hand down your pants. Oh wait, those last two were for my 6 year old.

Keep working out. Keep working out. Keep working out. I suspect most people reading this already have the desire to exercise regularly, but there are a few folks that might become a little more flaky now that their routine is disrupted. You can’t let that be an excuse. You can’t let change stop you. Your spouse might have to tolerate watching the kids for an 20 extra minutes. Big deal. We all have excuses. If you need a routine, make a new one. It’s New Year’s resolutions, part two, baby! Be adaptable and resilient. If you can’t obtain the same amount of time to exercise as you previously did, remember a little exercise goes a long way. Break it up through the day if you can’t get a single bout. If it’s less than 4 hours between, it’s similar to one bout as far as your recovery goes anyway.

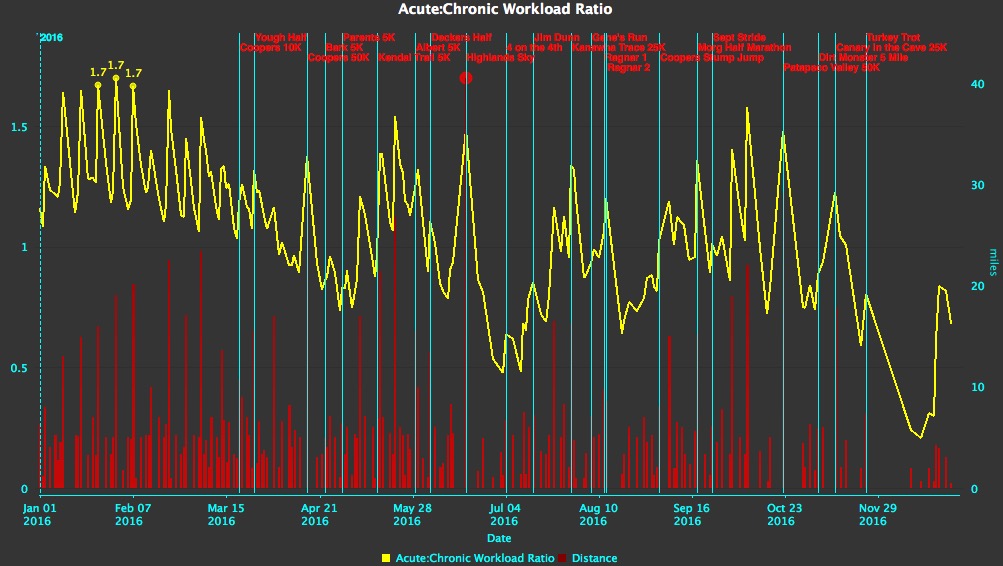

But don’t do anything silly if you have some extra time! If you’d been exercising 3-4 hours per week, don’t automatically jump to 8-10 hours of the same thing just because you are bored. Otherwise, you’ll set yourself up for injury, and while I’d love to have you in my office, injury prevention is ideal. I get that the exercise provides a psychological security blanket, but it’s not worth going overboard. If you do have extra time because your commute is gone or you locked your kids in the basement, you can ramp your volume up gradually by about 30 minutes each week for things like very easy running or hiking. You can get away with more time each week if it’s naturally less hard on your body, like cycling or elliptical.

Involve your family. Childcare can be hard to come by so let’s get those kiddos moving right along with you. You’ll all sleep better and maybe you’ll be a little less likely to lock them in the basement. Did I just say that again?

Eat well. Comfort foods? Moderation my friends. Whole foods as best as you can obtain. Don’t raid the junk food cabinet in a moment of weakness because then you’ll not only feel bad but then have to go to the store to get more junk food and you’ll be exposed to more virus carrying people. Coronavirus and Snickers or ration the Kit Kats. Your choice.

Don’t go crazy on the alcohol. Moderation my friends. Again. Do you want your kids' memory of this nonsense to be the time mommy got blotto and tried to teach math but then promptly fell down the stairs and broke her wrist? Didn’t think so. Our situation is not going to be improved by poor sleep and feeling gross either.

Practice good sleep hygiene. Try to stick to your normal sleep habits as best as possible. No screens past whatever o’clock works for you.

Go outside! It’s getting warmer and the days are getting longer. Even a warm rain is pretty tolerable if you have the right equipment. Just try to appreciate your surroundings in whatever conditions Mother Nature conjures up. There are so many articles encouraging us to exercise outside because the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission in the outdoors is very low. I can tell there are fewer vehicles on the roads right now, so let’s hope the air is a little cleaner for breathing. Though I heard a really bizarre thing about people trying to blame runners for spreading the virus throughout the public because they are breathing so deeply during a workout. Seriously?

Use your extra fitness from the buildup to an event that’s been cancelled. I’ve had events rescheduled or cancelled in the next couple months. I don’t like it either, but it’s not about me, it’s about the greater good of the public. Many of us like to have an event goal or we mentally wander, we feel less productive, we get hurt from overdoing, or we lose motivation. Run an FKT or make up an adventure run. Being a map nerd, adventure runs are nearly a weekly occurrence for me. Let me know if you need tips.

Do the maintenance and recovery work you keep putting off. Break out the roller, trigger point release all the muscles you neglect, stretch your terrible hip flexors. Try yoga. Try meditation. Oh, and strength train. Even 5-10 minutes of lifting something you would call heavy is worth it. It doesn’t have to be fancy. For resistance bands, old bike tubes actually work really well. Sand bags or sand in a milk jug makes decent DIY hand weights as will a bag or bucket filled with soup cans. Drag an old tire. Body weight exercises are always a possibility and I’ve seen 20 blog posts on that already. I’ve written about strength training a few times on this blog.

Maybe it’s time to build out that home gym or garage gym. Be realistic though. Don’t buy a bunch of unnecessary equipment you won’t use, especially with financial limitations being a possibility in the next few weeks. A medicine ball and a couple weights can accomplish a lot, especially when you work one arm or one leg at a time. My new favorite toy is a MOBO board. Never underestimate the power of learning to move your body better.

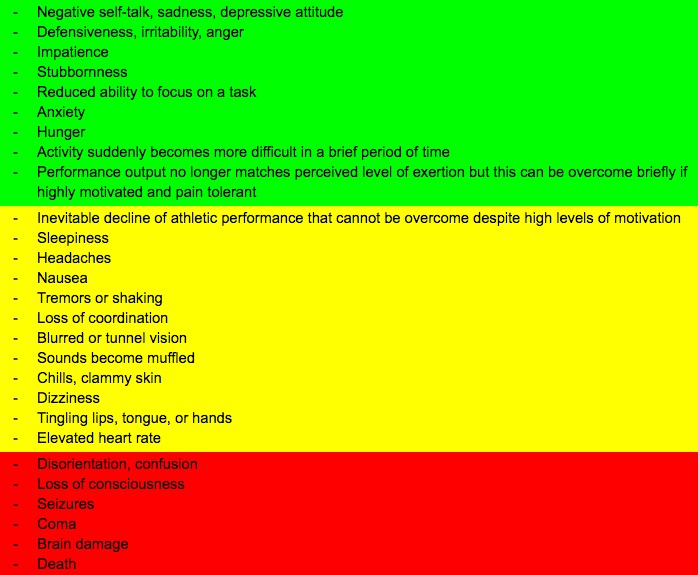

Just move and move often. The less you move, the crappier you’ll feel. Especially if you are accustomed to being really active, I guarantee it. We are built to move. It doesn’t even have to be exercise in the sense that you are most familiar. What sounds like fun? Be creative. What would you have done for fun when you were a kid? Kickball? Soccer? Bike ride? Hula hoop? Hop scotch? Just move. This is one of the most powerful things you can do to prevent illness by using your full lung volume, encouraging lymphatic flow, and maintaining/improving your immune system. You’ll be glad you did it. You won’t stay sane by staying so myopic.

Get a friend or coach to hold you accountable to staying active.

Go camping. Consider it apocalypse preparation practice. It’s pretty good at helping you realize what you need instead of what you want. Just don’t go too far from home in case you absolutely need to bail.

Take up trail running. I seriously have no idea why this one entered my mind. *Writer smiles in a smug and annoying way.*

Don’t get too sucked in by the media. It’s good to stay informed, but it’s too easy to drown in the negativity if you keep checking social media and the news every 10 minutes.

Think beyond your typical coping mechanisms now that your stress level is inevitably higher. Meditation. Writing for pleasure. Reading for pleasure.

Please share this list with those who would benefit from it! AKA everyone.